I first visited the Benedictine Abbey of Maria Laach in 1967. I was then a graduate student in England, a childhood friend was a monk there, and this was the first opportunity for us to reconnect since age 12 after my family moved to Canada 14 years earlier. I returned there over and over again for a day or three, or as much as a week, each time I was in Germany for the next 35 or so years. Were I to write the history of my spiritual development, Maria Laach would have a very prominent place. It is not far west of the town of Andernach on the Rhine, in the Eifel mountains, and on race days you can hear the cars on the Nuerburgring Nordschleife. (I only throw that in because Fr. Matt and I both follow Formula 1 Grand Prix racing, and the Nordschleife is a legendary race track, which sadly is no longer used for Formula 1, because it is not safe enough at the speeds involved.) Other than race days, Maria Laach has been a quiet place in which to unwind, a place for spiritual discernment, and it has provided a retreat, a community of faithful people with whom I could worship, reflect, and study, with my friend and some other monks being listening ears and guiding hands along the way.

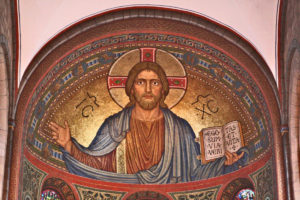

Benedictine monks from Beuron in southern Bavaria settled on the shore of this volcanic crater lake called Laach (which simply means lake in early German) in the late-11th century, and except for 90 years following the secularization of monasteries under Napoleon in 1802, Benedictines have lived and worked and prayed there ever since. While the monastery buildings are relatively modern, the basilican abbey church, dedicated to Our Lady Maria of Laach, is more than 900 years old. It is of Romanesque style; thick stone walls, and high-up, small windows. The interior is dark, cool, and shaded, heavy pillars supporting a barrel-vaulted roof. In the 20th century electric lighting was carefully installed, to highlight important parts of the church, but also to preserve the original dark quality. The high altar is in a large apse (a semi-circular space), and the stone table is surmounted by a stone canopy supported on four slender pillars (called a baldachino). Lighting has been installed into the canopy, illuminating the altar from above, and incidentally, or probably not so incidentally, making for an interesting “veiled” effect when incense is used at Mass. High above this altar the roof forms a large quarter sphere, and in this is a brightly lit mosaic portrait of Jesus as Christus Pantocrator; Christ the Judge of the world. (From 1911-although it is based on a much older Byzantine mosaic in Monreale Cathedral near Palermo, Sicily, done in the late 12th century.) Jesus is shown as a young man, with a highly decorated nimbus (halo) in the Greek style, wearing rich robes. His right hand is extended in blessing, and in his left hand he holds an open book on which is written (in Latin) “I am the way, the truth, and the life”.

(Worshippers had a black and white reproduction of the mosaic on their leaflets.) The most striking things about this mosaic portrait, helped by the careful lighting, are the eyes of Christ. They are wide open, and slightly larger than strictly proportional to the face, and no matter where you go in this very large space, they are looking directly at you. In this place, in this church, you cannot escape the eyes of Christ!

It is this kind of Christ, majestic, glorious, judging, that we hear about in today’s Gospel. The Parable of the Great Judgment is a familiar one, so familiar that it has entered our language, and everyone, practising Christian or not, seemingly knows what is meant by “separating the sheep from the goats.”

The setting is the end of time. Christ has returned to sit in glory upon a throne, surrounded by angels. All the nations of the earth are gathered before him, and then, like a shepherd separating sheep and goats out of a flock, the people are divided into two groups. One group is called blessed and destined to enter into the kingdom of God, the other is called cursed and destined to join the devil and the demons in that eternal absence of God called Hell.

It is the basis for separation that ought to be of particular interest to us. Remember, this is a parable, and it is a property of parables that they turn some commonly held notions upside down. Also, Jesus is speaking to 1st century Jews, and it is some of their commonly held notions he is turning upside down. So, we might look at some of the beliefs held by Jews then that Jesus is challenging!

One group, the Sadducees, believed that there was no immortality of the soul, and hence no final judgment. Living life by religious law was one’s duty, and a matter of discipline, but with no ultimate consequences. Another group, the Pharisees, believed in a final judgment, in which one would be evaluated on having kept all the many hundreds of religious rules and laws; breaking even one, even once, could and likely would result in eternal condemnation.

Then there were groups that believed only Jews were God’s chosen people, and all others would be condemned at a final judgment. These included some that believed simply being a Jew was enough, while there were others who argued that some degree of morality during life, more or less, was required. And there were others that believed that only by separation from society and lives of heroic holiness, including constant fasting, physical discomfort, and extreme religious practices, could one hope to win God’s approval and blessing.

It is beliefs such as these that Jesus is challenging. But he is also speaking to us, and challenging us, because these beliefs, with very little translation, can be found in our time.

It is not difficult to find people today, Christians or not, who do not believe in eternal life as orthodox Christianity teaches it. For such, living a moral life may be a matter of societal convenience, part of the structure of our culture, enforced by our laws, because we all get along better if everybody lives by the rules. Or they may live by the rules of “self-ism” where the individual determines how they will live, based on what feels good, or what is best for oneself. Morality is based on personal decisions, convenient consequences, situational ethics. All things are relative in the minds of such people.

But, Jesus says, ultimately, how one decides to live does matter. Jesus, in this parable, says “NO!” to thinking that we have a choice about how we live that is only ours, not subject to external, eternal rules. There is a final accounting, he says; how one lives in this earthly life has eternal consequences.

Then there are groups within Christianity who believe that life has to be lived according to a complex (and different, depending on which of them you ask) set of religious rules. All life is ordered, there are lists of things which are required, lists of things which are permitted, and lists of things which are forbidden, often with some being more required and others more forbidden than others. One’s ultimate fate depends on keeping all the many regulations which such groups hold important. Jesus again says “NO!” to such thinking. One’s final fate is not based on living according to a complex set of rules, it is based on something much simpler.

Then of course we have Christians today who think of themselves as “chosen” in one way or another. Belonging to the select may be based on some event in one’s life, or on having some particular religious experience, or by doing some particular religious act. Having once joined the chosen, such groups argue that one is automatically entitled to be called blessed at the final judgment, while everyone else is cursed.

Some groups believe that one must live lives of outstanding holiness, by their definition, in order to pass the final judgment. They require separation from the world, limited or no contact with those outside their own group, and perhaps rigid adherence to a complex set of religious practices. Sometimes this requires rejecting at least some of society, and living according to the standards of some past, supposed, golden age. And again Jesus says “NO!” to that kind of thinking in this parable. The judgement at the end of time is an individual one, each person is judged on their own life, there are no chosen groups, and there are no religious heroics which will earn entry into the kingdom.

The reality and basis for the final judgement is made brutally clear in this parable. All humanity will be judged, no matter what race, or nation, or group they come from. Everyone will be separated into one of only two groups, those that are blessed, and those that are cursed. And the basis for the judgement will be whether or not we cared about our fellow human beings, and whether or not we acted on that caring. The judgment is not between those who believe or don’t believe, not between those who act religiously or don’t act religiously, not between those who belong to some select group or don’t belong. The judgement is between those who care, and those who don’t care.

You might want to notice how the judge of the parable, who is of course our Lord, makes his judgement. We are judged on actions which every one of us is capable of doing. We cannot offer the excuse that we don’t have the intellect, or the understanding, or the resources to do these things. We can’t even argue that no one told us what the requirements were! For some parts of our lives that may well be so, but meanwhile the essence of what God demands from each of us is absolutely simple and clear.

Can I feed someone who is hungry? Can I give a drink to someone who is thirsty? Can I welcome a stranger? Can I give clothing to someone who is without it? Can I care for someone who is sick? Can I visit someone who is imprisoned? Can anything be simpler or clearer as instructions for following our Lord?

Notice the surprise of everyone in the parable, both the blessed and the cursed, when our Lord points out to them that when we serve others we serve him. Our Lord is telling us again that our relationship with him is a part of all our life, all our relationships, all our experiences, not something that just happens on a Sunday. Whatever we do or neglect to do, wherever, he is affected. Somewhere, in every moment, or place, or event, Christ is present, even if only to weep for us at our neglect of him.

Our Lord is a hidden Lord, always in disguise. He is the beggar on the street to whom we can give our coins. He is the unemployed person downtown at The Working Centre whom we can help with our gifts. He is the refugee without a home with whom we can willingly share the blessings of this country. He is the homeless man living at House of Friendship, whom we can house and feed with our support. He is the street kid who shows up at an Out of the Cold shelter when our Winter begins to bite. He is the homeless lady at the clothing bank looking for warm winter clothing which we can donate. He is the person with a terminal illness whom we can visit and comfort, or assist by donating to palliative care hospices or research. He is the starving third-world child whom we can feed with our money given to any number of agencies working in hunger relief. He is the disaster victim somewhere in our world for whom we can donate aid. He is the pregnant teenager at St. Monica House whose Christmas we can make somewhat more happy with a small gift. He is the hungry child at a breakfast club that we support. And, he is the perfectly well-off person, totally satisfied with themselves, with no need of a saviour or change in their lives, whom we are called to challenge and call to faithfulness!

While always hidden and in disguise, our Lord is always present and perfectly visible. He is everyone we meet, and he is especially those who need our care and love and service, and even those who need our challenge! If we for one minute believe that humanity, all humanity, is made in the image of God, then everyone we meet, regardless of class, status, condition of life, regardless of any categories we set up, everyone, everyone we encounter is Christ!

Like the majestic Christ in the Abbey Church at Maria Laach, his eyes are always on us. Our prayer is that our eyes may be opened to know him, and knowing him, that our hearts may be moved to serve him.

Copyright ©2017 by Gerry Mueller.